Here are the answers to 6 of the top 7 questions we get about exercise, specifically from our female clients throughout their exercise journey. The over-riding question, does my menstrual cycle affect my adaptation and performance at exercise or sport, rates its own blog to come soon.

- Will lifting weights make me bulky? Just like for males, it depends on the dosage rather than just participation. Driving each day won’t turn you into a professional race driver. Visually observable muscle growth only occurs with large dosages or volumes of more than 10 very difficult sets per week per muscle group. I won’t lie and say you won’t grow any muscle when you start lifting because you will, which is part of the reason lifting weights is a healthy lifelong exercise. However, visual increases in size can be reduced by completing less than 10 sets per week for a body part. You will still reap the other benefits of lifting weights, such as improved strength, mood and body image, and general health. If your muscles grow more than you want, complete fewer sets each week (move those sets to another body part), and train that body part last in the session, and the muscles will become smaller again. Encouraging all this, sceptical women who choose to start lifting will notice becoming more “defined” or “toned” and, in response, independent of our advice, will intrinsically increase the amounts of lifting they do to reap more unexpected improvements in perceived body image. Also, if you don’t want to look visually bigger like the female bodybuilder you might be picturing, avoid increasing food intake and performance-enhancing drugs.

- Does being a woman make me less able to improve muscle size and strength than being a man? Females who might be starting or struggling to increase their muscle mass or strength with lifting often are misled by another social stereotype that men increase muscle size and strength faster than females. This is very, very untrue. Across hundreds of training studies, we have observed males and females increase muscle size and strength with the same training program timeline, the same amount. This widely published data has not become a cultural norm for some reason. For males, they start larger and stronger (but not always), and their absolute values of muscle mass and strength that increase are larger, but the relative values are, on average, equivalent between sexes. For example, a female might start with a 30 kg squat and have an absolute increase of 10kg or a relative increase of 30% in strength across 10 weeks. For a male who starts at a 60kg squat, I’d also expect a 30% increase with a similar dosage of resistance training, but the absolute change would be 17kg, appearing greater than the female but is the same relative increase. But what about testosterone? Well, testosterone explains a significant component of the starting point differences, but changes in testosterone in response to exercise do not predict changes in strength or muscle growth for either sex. Increasing your testosterone response after exercise is overrated for long-term muscle size and strength gains. Visit this review for more about the equivalence of training response between sexes, which also showed a trend that females might be able to gain relative upper body strength faster than males. Re-examine your training volume, intensity, recovery, sleep, and lifestyle stress, or seek coaching assistance to identify more accurate lifestyle or training factors leading to progression plateaus.

- “Do oral contraceptives affect exercise performance or adaptations?” Historically, in some countries, sports coaches falsely forced female athletes to take oral contraceptives with the belief that hormone stability would improve performance. Many women, outside of not wanting to become pregnant, might appreciate the pill due to changes in their symptom profile that might positively affect their experience of exercise. But does that consistently allow superior performance or exercise adaptation compared to non-pill users? Multiple high-quality reviews showed that oral contraceptives seem to have minimal effect on performance outside of the individual-reported side effects of the different types. See this review and this review for more. No one should be confident to assume that the common types of contraceptive pills will be helpful or harmful for exercise performance and adaptation.

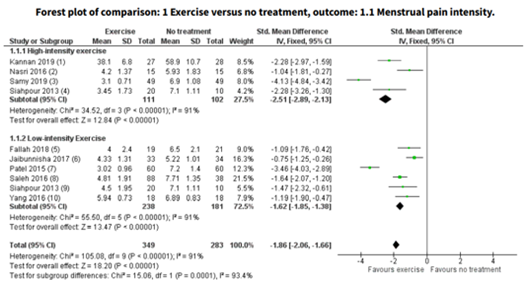

- “Does exercise help with period pain?” Mild to moderate intensity exercise will not make your period pain worse. The best systematic review we have on the topic to date, published in 2019, concluded that exercise, performed for about 45 to 60 minutes each time, three times per week or more, regardless of intensity, versus not doing any exercise, may provide a clinically significant 25% reduction in menstrual pain intensity on average. The modes studied included aerobic training, Zumba, stretching, core strengthening, and yoga. Resistance training was not assessed. We believe exercise is helpful during and before your period due to its positive effects on mood by reducing cortisol and increasing serotonin and dopamine, reducing perceived fatigue and cramps while potentially reducing inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins, which are linked to increased period pain and cramping (why Nurofen or another oral anti-inflammatory can be helpful). Start with a light walk for 5-10 minutes a couple of times each day for the bad days if you are unsure where to start.

(Armour et al., 2019) Of all high quality studies assessed, all favoured exercise versus no exercise.

- “As a female, I’m predisposed to injury? Like, look at ACL injuries in females injury risk.” First, fear of injury is a risk factor for injury, so any intrinsic belief in fragility should be managed to lessen injury risk. Yes, women are at a greater risk of ACL injuries. But don’t be concerned that most of the risk for ACL injury associated with being female is not modifiable. Sport and agility training experience and strength are predictors of injury to the knee, which can be controlled by training exposure. My personal experience has come from communication with coaches within the West Australian Football League Women’s Association, who for years have consistently highlighted the lack of funding, financial support, or time given to female footy players that is allowed for the men’s teams to support increased training exposure. Hormone-related theories for the hormone relaxin released during the luteal phase and its effect on ligament laxity have not been firmly proven (Review), and ACL risk has not been correlated to any specific menstrual cycle phase. See this review from this year to read more. Additionally, for every musculoskeletal condition that could be associated with or without tissue laxity that females are at increased risk of, such as hip tendon pain, neck pain, and osteoarthritis, we could list an injury that males are at increased risk of like muscle strains, MCL strains (another knee ligament) and shoulder dislocations. Focusing on your unmodifiable sex-related factors is not helpful or encouraged in deciding what physical activity you want to participate in. If you are concerned about your injury risk, seek well-informed advice for modifying the modifiable so you can be optimistic and confident to focus on your performance in the gym or the sporting arena.

- As a female, should I eat differently from males? Women use more fat, less carbohydrate, and less protein than men during the same exercise intensity. Still, the application of this outside of an exercise physiology lab is overrated for determining daily consumption of these macronutrients. Most differences in daily energy expenditure or metabolic rate between males and females can be explained by muscle mass, fat mass, and physical activity level. We encourage seeking an individualised approach to dietary choices following general recommendations from the Australian dietary guidelines around building a variety of sustainable (both environmentally and concerning timespan) dietary options to fuel your exercise requirements and improve your enjoyment of food.

Hopefully, you didn’t feel too much “mansplained.” Let us know if you want to hear more about any of the above questions in more detail or have other questions related to your sex and exercise.

Written by Tom Murphey, DPT.

“Unfortunately for our community, scientific scaremongering is common, easy to believe, and hard to heal. Research is often messy, and strong stances or beliefs can be erroneous and dishonest. I aim to produce honest reviews of high-quality research to provide informed insight so you can make up your own mind on the science you value.”

References.

- See text links throughout the blog.

More resources

https://bjsm.bmj.com/pages/bjsm-e-edition-female-athlete-health BJSM E-edition: Female athlete health

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspor.2023.1054542/full#:~:text=The%20authors%20showed%20that%20the,not%20affect%20strength%2Drelated%20outcomes. “Current evidence shows no influence of women’s menstrual cycle phase on acute strength performance or adaptations to resistance exercise training”

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-019-0152-7 Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7916245/ The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review

Comments:

share