At Ace, clients sometimes ask our opinion on various dietary supplements to assist their exercise goals. Based on the cumulative nutrition evidence, we recommend that if you are to consume any supplements to aid your exercise goals, pick creatine monohydrate, protein power and caffeine. We will address the benefits of these supplements in the future, but todays blog is about, creatine, one of the few beneficial supplements on the market. The best-known function of creatine supplementation is to increase its immediate availability to your muscle, which allows improved rapid resynthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is the chemical form of energy that cells need for exercise. Less commonly known is that creatine influences helpful inflammatory signals and increases muscle glucose and other growth regulators within muscle cell which all assist further with muscle growth (more specifically called hypertrophy in exercise science) (Chilibeck et al., 2017). When paired with progressive exercise training, long term studies all show benefit of creatine in improving muscle strength, power output and general exercise performance (Antonio et al., 2021). Burke and colleagues published a review recently outlining all the benefits and recommended dosage of creatine to assist in muscle hypertrophy as measured by direct imaging with ultrasound or computed tomography. What was highlighted includes:

• Of the 10 studies included, most implemented dosing protocols of 0.1 to 0.15 g/kg/day of creatine, ingested 5 to 7 times a week while muscle hypertrophy driven resistance training was completed between 2 to 5 times a week. The long-term training studies ranged from 6 to 52 weeks of supplementation. Only one study that was reviewed investigated only women and only 2 studies looked at resistance trained participants (definition not given within the review) limiting who the results can be applied to. “Responders” and “non-responder” were not delineated.

• Creatine supplementation when compared with a placebo, increases lower and upper body muscle mass equally, by a small amount. Other studies that have shown a more significant effect was most likely influenced by how muscle hypertrophy was measured which does not account for increases in fluid in the extracellular space around the muscle, thus giving the illusion of greater muscle hypertrophy. In contrast, the small effect of creatine supplementation could have been due to the lack of delineation between “responders” and “non-responders” in this review.

• Creatine supplementation was found more effective for younger participants (mean age: 23.5 years) rather than older adults (mean age: 61.6 years) potentially due the ageing effect on shifts in reduction in size of type II muscle fibres which has been attributed to the 20-30% of people who are “non-responders” or don’t report benefits to creatine supplementation.

• A trivial difference favouring increased benefits in shorter vs longer creatine supplementation training studies. However, all longer length studies were completed by older individuals, which if they were most likely “non-responders”, could be a confounding factor potentially attributing to a lesser effect due to age rather than supplementation duration.

There are some other points we would like to cover before finishing related to common concerns about creatine. Antonio et al. (2021) explains the origins and falseness of some beliefs around creatine and is a great article to check out further. Common beliefs about creatine that are false which you should not be concerned by include:

- “Creatine is a steroid”. It’s not. This is like calling glucose a steroid.

- “Causes significant water retention, dehydration, or cramping”. Non-significant inconsistent effects are most apparent across the literature.

- “Causes balding”. It doesn’t.

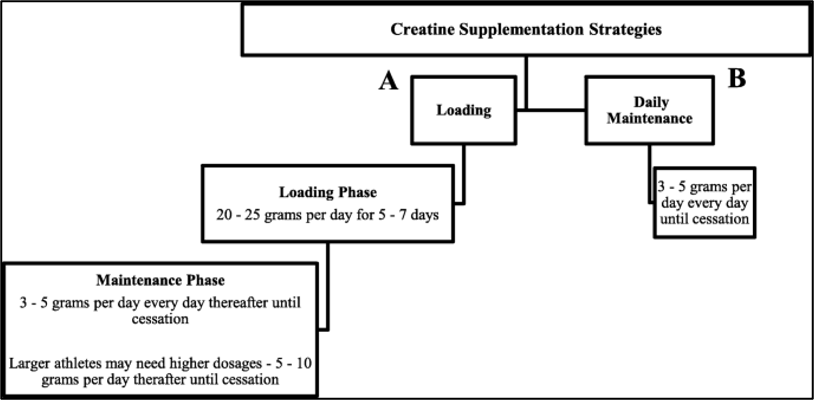

- “Follow a “loading phase” or ingest 20g per day for 5-7days before 5g per day maintenance dose”. In comparison after 4 weeks, a dosage of 0.1 or 0.15 g/kg/day initially has equal muscle saturation effects compared to a “loading phases.” You do not need to complete a loading phase.

- “Has only short-term benefit and should be cycled off”. This is similar to saying sugar loses its energetic effect long term. Consistent long-term supplementation remains effective.

- “Unsafe for kidneys or the gastrointestinal system”. Not at dosages of less than 10g/day of long-term supplementation as suggested.

- “Unsafe/ineffective for women, children or people older than 55”. Growing body of evidence showing muscular, neurological and performance benefits in all these populations but as noted earlier, more work is required.

- “Creatine monohydrate is not the most effective type of creatine”. Actually, any type other than creatine monohydrate is likely to be a less suitable choice despite differences in solubility.

- “Timing of ingestion around workout matters”. Nope. No effect of timing according to Ribeiro et al. (2021).

Why might you be a responder or non-responder? Responders to creatine might have increased type II muscle fibre types, larger muscle fibre cross sectional area and increased fat-free mass (Syrotuik et al., 2004). This suggestion is unproven but as these body composition characteristics are all adaptations to resistance training, continue completing resistance training and creatine might become more beneficial as you become more “trained”. Creatine is not expensive comparted to other less effective supplement, so we don’t think you are wasting your money if you are currently a non-responder. Just keep your expectation small as if you were a responder anyway and consume the dose of 0.1 to 0.15 g/kg/day as more is not better.

Overall, the practical significance is creatine supplementation is proven to be effective for increasing muscle growth above what it will increase anyway when you are consistently training progressively, but its effect on muscle growth is only small. And this is one of the most effective supplements for muscle hypertrophy. Consider this when choosing to spend your money on other supplements!

(Antonio et al., 2021- recommended loading strategies)

Written by Tom Murphey, DPT.

“Unfortunately for our community, scientific scaremongering is common, easy to believe and hard to heal. Research is often messy, and strong stances or beliefs can be both erroneous and dishonest. I aim to produce honest reviews of some high-quality research to provide informed insight so you can make up your own mind on the science you value.”

References

Antonio, J., Candow, D. G., Forbes, S. C., Gualano, B., Jagim, A. R., Kreider, R. B., … & Ziegenfuss, T. N. (2021). Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show?. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 18(1), 13.

Burke, R., Piñero, A., Coleman, M., Mohan, A., Sapuppo, M., Augustin, F., … & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2023). The Effects of Creatine Supplementation Combined with Resistance Training on Regional Measures of Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 15(9), 2116.

Chilibeck, P.D.; Kaviani, M.; Candow, D.G.; AZello, G. Effect of creatine supplementation during resistance training on lean tissue mass and muscular strength in older adults: A meta-analysis. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2017, 8, 213–226.

Ribeiro F, Longobardi I, Perim P, Duarte B, Ferreira P, Gualano B, Roschel H, Saunders B. Timing of Creatine Supplementation around Exercise: A Real Concern? Nutrients. 2021 Aug 19;13(8):2844. doi: 10.3390/nu13082844. PMID: 34445003; PMCID: PMC8401986.

Syrotuik, D.G.; Bell, G.J. Acute creatine monohydrate supplementation: A descriptive physiological profile of responders vs. nonresponders. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 610–617.

Comments:

share